Valsesia and its “Ribeba”

A forgotten jew’s harp production center

La Ribeba in Valsesia nella storia europea dello scacciapensieri (English translation: The Ribeba in Valsesia in the European jew’s harp history), published in August 2019 by LIM (Libreria Musicale Italiana - Lucca), is the first complete monograph about ancient jew’s harp production in Valsesia.

The work, which is written in Italian but includes an English Abstract at the end of the book, is structured in fourteen chapters and analyses the history of the Valsesia jew’s harp placing it within a more complex Italian, European and Global jew’s harp context.

It was only in the second half of the XX century that the Italian jew’s harp traditions (both manufacture and playing traditions, as, for example, in Sardinia, Calabria or Sicily) were studied systematically. In the first part of book, therefore, the authors explore the complete history of Italian jew’s harp studies from nearly 200 years of anthropological and ethnomusicological studies in Italy.

The book then focuses on the Valsesia jew’s harp production using as a source local historians, the oral memory of the local people, and historical and archival records.

From the late XV to the late XIX/early XX century, there were several smithies in Valsesia, an alpine valley in the Piedmont region of Italy. These produced millions of instruments (in the four centuries of production we can estimate something like 140 million instruments) and exported them not only in Europe but also to America. This case, in many ways very similar to the other “alpine” production center of Molln in Austria, is now told with the invaluable aid of recently discovered historical documentation, found in both public and private archives. The production is not only exposed in its mere economic aspects but also in its social, anthropological and cultural ones: for example, from ancient documents there is a 1790 trial concerning a quarrel between jew’s harp smiths and merchants, caused by the forgery of the punch marks used on the instruments. From this it is possible to grasp the importance of such a curious instrument making industry for an alpine community and, most importantly, provides a vivid and realistic look at the life and society of the period.

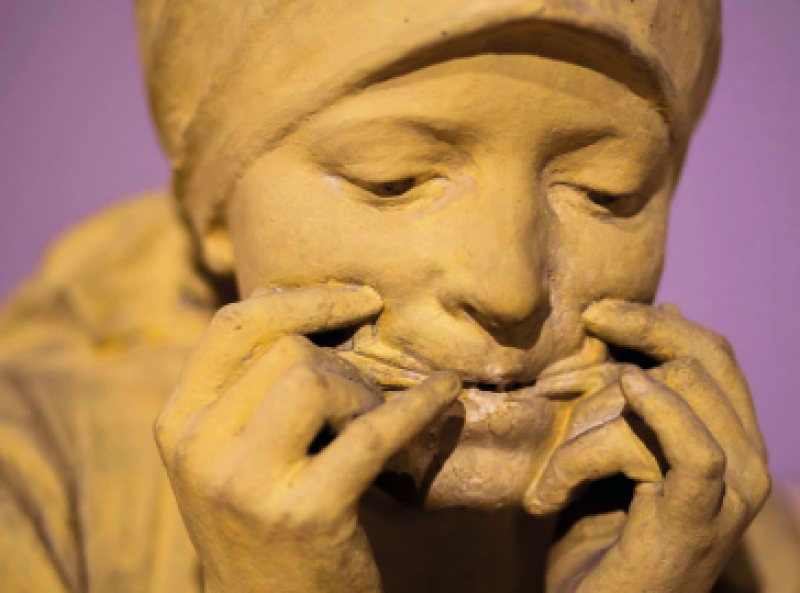

A ribeba with a “L” punch mark on the side of its frame. Property of Guido Antoniotti, photo by Matteo Zolt.

An entire chapter is dedicated to a linguistical analysis of the jew’s harp name in Valsesia and in Italy: nearly every Italian dialect has a name for such instrument and, especially in the Northern regions, the jew’s harp dialectal name is very often used as a “double entendre” reference to female sexuality or to describe obnoxiousness, recalling the monotonous sound (zanfornia, ciampornia, ciornia, rebeba etc…). In the Southern regions the name of the jew’s harp can contain some very interesting references to the “margins” of society such as Romani people in Campania and Calabria (chitarra de li zingari, tromba degli zingari) (who, still today, manufacture jew’s harps in those regions) or criminals and brigands in Sicily (gangalarruni, malalarruni, mariolu).

The traditional musical use of the instrument in Valsesia gradually disappeared with the end of the production, and left few, though very important traces in literature and iconography. By analysing them it is possible to assume that the jew’s harp was widely played in the valley sometimes using “virtuoso” playing techniques (e.g. two instruments played simultaneously). Some hints of “magical” and “alchemical” beliefs around the jew’s harp, very similar to ones found in Austria, Sicily and Sardinia, were also found in Valsesia.

From an organological point of view, the book contains an accurate analysis of the morphological features of the “valsesian ribeba”. This can be useful to finally recognize the Valsesia jew’s harps among the great number of European jew’s harp forms and types. One issue worth a short, though important chapter, is the punch mark: these were intended, as in the Molln production, to protect the products of individual makers.

The final chapters discuss the presence of the Valsesia instruments in private collections and museums and the rise (and fall) of the ribeba as a local cultural symbol for the Valsesia region and its inhabitants. In the last chapter the authors mention the recent attempts to reproduce jew’s harps in Valsesia, made after the end of the “historical” production, as to further communicate the hope that the ribeba will resonate again in this part of the world.

Three ribebe with a wooden case. Property of Alberto Lovatto, photo by Matteo Zolt.

Fragment of a live performance by the authors Alberto Lovatto and Alessandro Zolt

Contact: alex.zolt@hotmail.it